- K

- May 1, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 17

A convertible instrument is both a liability as well as equity.

Accounting for it as a liability requires us to look at this instrument in the form of debt. To value debt, we discount all future interest payments and the principal repayments using the coupon rate to arrive at a present value.

The present value of these cash flows are lower than the face value of the size of the CB because of the discounting effect. Hence, the difference between this present value and the face value of the CB is gives its corresponding equity value.

But why bother splitting up the liability and equity components?

Say a fast growing company is looking for additional funds to expand its business. The owners do not want to raise equity because they prefer not to dilute the shares of the company. One option would be to borrow a loan from the bank, and for simplicity, let's assume that the bank quotes them an interest rate of 12%.

Alternatively, the company could also raise this money by issuing a convertible bond, which allows the company to offer fixed interest payments, while providing flexibility to convert the principal into shares of the business.

Investors can enjoy fixed income from the CB's interest payments (the debt portion) while getting potential upside should the company do well (the equity portion).

Comparing this structure with the 12% cost of funding of the plain vanilla loan, how should investors price the CB?

Because the company is allowing investors to potentially benefit from having a share in the business, there has to be some trade-off when comparing this funding option to a simple loan. And it only makes sense to issue a CB only if the interest rate is lower than 12%, right?

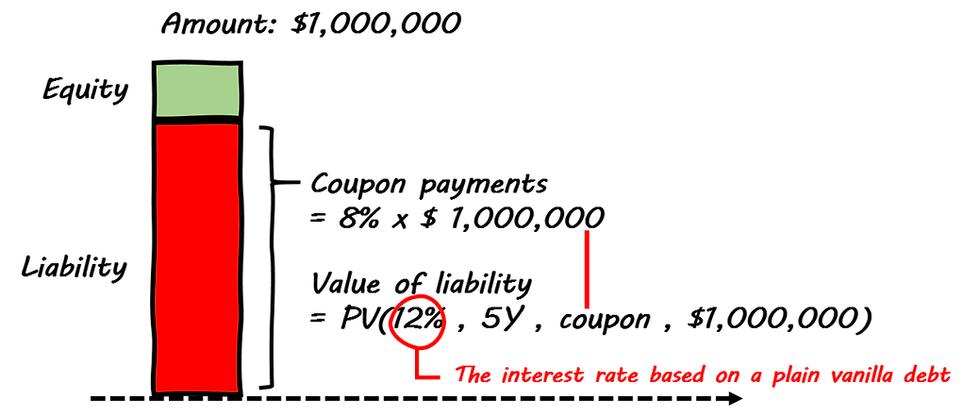

Ok let's assume the CB is priced with an interest rate of 8%. Before the loan gets repaid or converted, the way both debt and equity components at the onset could look something like this:

To correctly value both the CB's equity and liability at the onset, we first treat the debt component in a CB like a plain vanilla bond, using the 8% interest payments as cash flows but discounting it with the 12% interest rate of a nominal plain vanilla debt:

So at the onset, the value of the CB's equity would simply be the difference between the the issue size of $1 million and the present value of the debt component cash flows.

The behaviour of a CB.

It is also logical that for every year the CB is not converted, the liability component increases, converging towards the value of the principal i.e. the amount that needs to be repaid upon maturity (just like a debt obligation with a 12% cost of funding). Note that over this period, there is no change in the equity value of the CB.

The cash flows of the liability component over five years would look like this:

For every year that the CB does not convert, the 12% interest (costs of raising a plain vanilla debt) is accrued (not paid) in the income statement, flowing straight to the company's retained earnings.

Now let's look at the alternate scenario in which investors swap the CB into shares. And let's assume this happens at the end of the third year.

Executing a debt-to-equity swap in year 3.

At the end of year 3, the liability component "zerorizes" due to the swap and the principal gets converted (capitalized) into equity on the books. A share premium (equity) get recognized as part of the conversion.

This premium is computed as the difference between the issue price of the CB and the outstanding book value of both the liability and equity components at the point of conversion

144,191 + 932,398 - 1,000,000 = 76,589Simply put: The equity premium reflects the perceived "benefit" in raising a 8% CB vs plain vanilla debt at 12%.

Editable worksheet: